“The vote and the results lack legitimacy,” U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson declared, referring to recent events in Kurdistan. Similar remarks were made by the U.S. ambassador in Baghdad, Douglas A. Silliman, and U.S. President Donald Trump’s special envoy Brett McGurk.

The American opposition to Kurdish independence take us back in time 70 years, when the leadership of the Jewish population in prestate Israel announced its plan to declare independence. In response, the U.S. State Department began working assiduously, sometimes making threats, to scupper that decision. Then-Secretary of State Gen. George Marshall, who was covered in glory after World War II, as well as the entire American foreign policy and defense establishment, took a firm stance against the establishment of the Jewish state.

Their official reasons (other than the anti-Semitism that was rife in the State Department and the defense and intelligence establishments) were very similar to Washington’s arguments against Kurdish independence – namely, that it will destabilize the region. Then, like now, oil factors into the U.S. position. Back in the day, American officials were worried that supporting the Jewish state would endanger the supply of Arab oil to America and its relations with the Arab world in general. This time, America is afraid that the Kurds’ intent to control Kirkuk, one of Iraq’s main oil-producing areas, will hurt the chance of it developing good relations with the government in Baghdad, including on oil issues.

Washington is trying to convince the Kurds that it only wants them to “postpone” their declaration of independence to a more convenient time, whereas in 1948, the U.S. administration – encouraged by the British Foreign Office – intended to thwart the establishment of a state by setting up a provisional international government in Palestine. Now the U.N. is also trying to persuade the Kurds to be satisfied with a compromise under which they would “postpone” independence in exchange for various rights and benefits as part of a united Iraq. In 1948, too, the U.N. played an active part when Count Folke Bernadotte suggested tearing the Negev Desert and Jerusalem off of Israel.

While the opposition of Iran, Iraq, and Turkey, which also have sizeable Kurdish minority populations, to an independent Kurdistan is clear, it is harder to justify the American administration’s position. Washington claims that the Kurdish declaration of independence supposedly hurts the war against the Islamic State, but the Kurdish peshmerga army aims to oust the Islamic State from the land Kurdistan wants to claim as its own. This interest will be even more important once independence is declared.

Aside from the moral aspect, it is difficult not to wonder at the mistake that is dictating the current U.S. position that preventing Kurdish independence and preserving the unity of the artificial Iraqi state will secure Washington’s influence in the region when in practice Iran is increasingly the one that is running the show. As with Israel 70 years ago, the new state – if it is founded – can expect violence from day one. Back then, it was the Arab states; this time, it will be the Iraqi government or possibly Iran and Turkey.

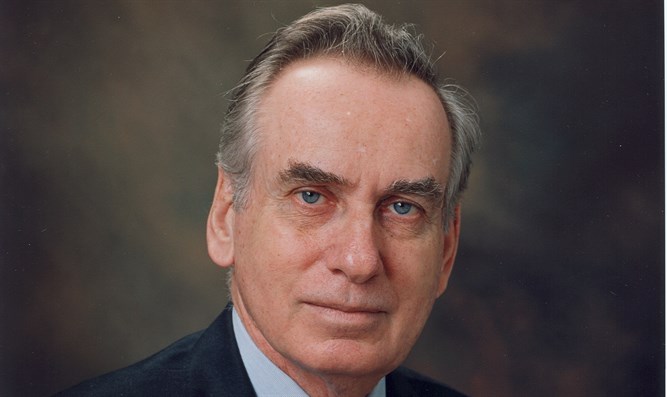

Back then, two people crushed all the schemes: David Ben-Gurion, who understood that it was an opportunity for the Jewish people that would not come again, and U.S. President Harry Truman, who despite the positions of most of his advisers decided to recognize the state of Israel as soon as it declared independence. Will Massoud Barzani, the undeclared president of the Iraqi Kurdistan, and President Trump follow in their footsteps?